The Old Mill is an important part of the industrial heritage and here we will tell you more about it and something of the story of the Ouseburn Valley – how the valley developed, the history and technology of watermills, and the changes brought by the Industrial Revolution. History, Ownership and Uses

Watermills were in use in the Dene from at least the 13th Century. Northumberland

Court records for 1271-2 mention a dispute over ownership of two watermills in

Heaton and Jesmond Vale by heirs to Adam of Jesmond. Although the exact location

of these mills is not known, it is possible that the Heaton mill was located at

the site of the Old Mill.

A water corn mill certainly existed on the site by 1739, owned by the Ridley’s and

known as Mabel’s Mill or Maboll’s Mill. Deeds record the owner as Matthew Ridley

and John Cutler was the miller.

The current Listed Building probably dates to the early 19th Century (before 1820),

possibly incorporating an earlier mill on the site and has been much repaired and

altered over the years

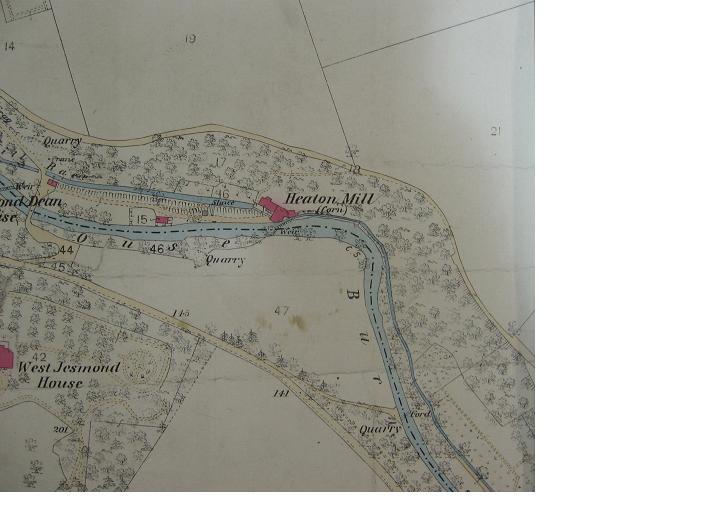

A map from 1800 shows a small structure on the site and names the land as belonging

to Batts and High Mill. A painting from 1820 shows the mill in its current layout

but with a large extension to the West (upstream). It was recorded on the 1st

Edition OS map as Heaton Corn Mill in 1858 by which time the extension to the West

had been demolished. By the time of the 2nd Edition OS of 1895 it was called

Jesmond Old Mill and so was out of use.

At about the time the current mill was built, the Freeman family from Gateshead

began a long association with the mill. Archibald Freeman was operating a windmill

at Windmill Hills, Gateshead and in 1795 his son Patrick (Paddy) Freeman moved to

Heaton and took over the mill as a tenant of Sir Matthew Ridley, still using it to

grind corn. He also took the tenancy of the 270 acre farm at High Heaton. In 1838

T.E. Headlam became the owner, with Paddy’s son, also Patrick, becoming the miller

by the time of the 1841 Census. The Freemans gave up the mill in the 1850s and by

1856 the mill was being worked by a Mr. Pigg who used it to make pollards (bran feed)

for pig feed from spoilt grain. By 1857 the next lessee was John Charlton who

converted the mill to grinding flint. The powdered flint was then transported to

the mouth of the Ouseburn for use as glaze at the pottery factories there. The

1861 Census shows that William Martin and his family lived at the mill. William

was a carter by trade and perhaps it is his family shown in one of the old photos

surviving from the period. William’s son, Thomas (aged 12) was shown in the Census

as an apprentice to the flint miller.

In 1862 the Sir William Armstrong bought the land in the Dene which included the

mill. Although still lived in until the 1920’s, milling ceased sometime between the

1860’s and 1890’s. The 1891 Census recorded William Thompson and his family were

living in Old Mill House – William and his son James were stone masons, perhaps

working for Lord Armstrong.

The Freemans remained in the area as tenants of Sir Matthew Ridley at High Heaton

farm until at least 1871 but by the time of the 1891 Census, they had moved to Cambois

Farm at Sleekburn near Bedlington. The farm at High Heaton later became the park

known as Paddy Freeman’s.

Also shown in the 1891 Census is the Thompson family living at the Old Mill. William

Thompson (aged 52) was a stone mason, as was his son James and it may be that they

were then employed working for Armstrong in the Dene.

In the early days of milling the mills were controlled by the Lord of the Manor or

the monasteries and they would exercise what were known as "soke rights". This meant

that all the tenants on the land were obliged to have their corn ground at the mill

and they would have to pay one sixteenth of the grain for the privilege.

However, this wasn’t fixed and millers often took more than they were due. They had a

reputation for being dishonest and were often said to have a "golden thumb", referring

to the practice of pressing their thumb on the scales to increase the weight and

therefore the price charged. It gave rise to the expression to get "soaked" or

overcharged.

It was customary for the miller to collect the grain from the surrounding farms in

his horse drawn wagon. The miller therefore came into contact with many people and

in the medieval period was a very important person in the village, third only behind

the lord of the manor and the priest.

The skills of the millwright were often passed down through generations of a family,

with the son taking over the mill from the father. He had to be a very handy person,

being able to repair all sorts of problems that could arise such as leaks in the mill

race or problems with the machinery. He may also have sharpened (or ‘dressed’) his

own mill stones although this was more often done by a skilled stone-dresser. It was

said that a water miller had to have an ‘eye’ for the flow of water, an ‘ear for the

sound of the stones grinding, a ‘thumb’ for testing the quality of the flour and

a ‘feel’ for the smooth working of the mill.

By the 18th century the mills were no longer in control of the landowners or the

church. The dissolution of the monasteries, the growth in the population and improved

transportation all led to the establishment of the independent mill, owned and run

by the miller.

In 1796, a law went into affect that made payment for the miller's services in

money compulsory. Prices had to be posted or the miller was fined 20 shillings.

This was done to eliminate the illegal practice of "hanging up the cat", in which

a miller took some of the farmer's grain for himself.

The start of the nineteenth century had already seen the beginnings of the industrial

revolution. Changes were happening rapidly throughout the country both in urban and

rural areas. In the country most families worked for the local landowner, as

labourers living on small cottages on his land. Others lived in their own homes

and had occupations such as blacksmiths, cobblers, millers and brewers. In this

period more and more families earned their living from industrial work, there was

a general movement of families from the country, where labourer’s jobs had become

fewer because of new inventions, to the towns where work could be found.

Children of the time were often put to work in the family business; they would be

expected to help in the general running of the mill although this would not have

been nearly as unpleasant as working down the pits as many children were required

to do. If they were lucky they would be able to attend school which would give them

an opportunity of a better future. They would often be trained as an apprentice,

to continue the family business – demonstrated perhaps in our mill by the three

generations of the Freeman family that worked the mill.

The miller’s cottage would have provided reasonable accommodation for the family,

being clean and dry (the mill would certainly have had to be kept in good condition

because damp conditions would spoil the grain and flour). The furniture would

probably be plain and only essential items present. It is also possible that the

cottage would have had a small garden where vegetables would have been grown.

The general changes to the country at that time also had an effect on the mills,

especially towards the end of the period. With the abolition of the Corn Laws in

1846, cheaper grain from abroad became available, and many village mills changed

their occupations around this period. Our mill changed twice: grinding pollards

(a food for pigs) then flint for the pottery industries (where it was used to whiten

and strengthen the pot and as a glaze). This would have implications for the families

living there; one sixteenth of the pollards or the flint would not have been much

use to the family. This could have been a downturn in the fortunes of milling

families; they had joined industry, where wages were notoriously poor.

Sandstone quarrying was one of several industries in the Dene and the mill was

probably built with sandstone from local quarries.

The mill was fitted with an overshot waterwheel and its water supply delivered by a

mill race starting about 500 m. upstream (near to the present Castle Farm Bridge).

It required a large earth embankment for much of this distance, but the final

20-30 m of the approach to the mill was in an overhead flume still visible in

older photographs. The water exited from the waterwheel above a weir constructed

to provide the water supply for the next mill downstream. The next mill race for

this began immediately, carrying the water for Heaton Cottage Flint Mill

(now Fisherman’s Lodge Restaurant). The mill race can clearly be seen in the 1st

Edition OS Map from about 1858. (reproduced by kind permission of the Ordnance Survey – Crown Copyright).